Is there any way to tell if you are overtraining? Is there anything you will notice?

Yes.

See: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Overtraining

For me the most pronounced symptoms are insomnia (takes a long time to fall asleep and sleep is restless) and more frequent colds.

See: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Overtraining

For me the most pronounced symptoms are insomnia (takes a long time to fall asleep and sleep is restless) and more frequent colds.

ok thanks i will read it.

bishop17

Banned

- Awards

- 0

Just don't workout a muscle thats still sore...even if its a little sore...thats a for sure way to avoid overtraining

allright thanks for the tip man.

Yeah that rings true for me. Not the sleep thing but colds, if I am rundown, body can't keep up with stress from gym, then the cold comes on quick, 2 - 3 day'r.

Hope this helps and "never stop seeking"

Much love,

Neoborn

Hope this helps and "never stop seeking"

Much love,

Neoborn

When I have absolutely no motivation to go to the gym I know I am over training because I usually look forward to hitting the weights. So I take 3-4 days off or do light volume and weight for 1-2 weeks. Often the best gains occur during this time.

I definitely have some pretty intense sleep issues when I overtrain. I'll either suddenly wake up right as my eyes are closing (for hours,) or I'll get very light sleep that doesn't really provide much rest :sad:

For the first 3-4 years when i started working out i was definatly overtrained. The first signs was my blood pressure gets high, my heart rate is high. I couldnt sleep at all. When i got to the gym i really didnt want to be there so i abused ephedra and caffeine to get myself motivated. I had a very very hard time getting as lean as i wanted to, even though i was lifting 1.5 hours and doing 1.5 hours of cardio :trout:.... I continued to ignore these symptoms and would end up developing tendonitis in my joints. I would also ignore colds and flus and continue to overtrain... i ended up getting pneumonia and thats when i turned myself around. I now workout for 45 minutes and maybe do 20 minutes of HIT cardio. It took me almost 2 years to finally get my body back to normal. WHen i was overtrained i was 190 pds and it was a struggle to keep my bf low. Now i am 220 and am leaner than i was at 190.

DriverDan

Member

- Awards

- 0

Just because a muscle is sore doesn't mean it needs more rest.Just don't workout a muscle thats still sore...even if its a little sore...thats a for sure way to avoid overtraining

really good advice, SteelEntity i no what you mean i really enjoy hitting those weights. And if i was overtraining i probably wouldn't.

bishop17

Banned

- Awards

- 0

It might the only for sure way thoughJust because a muscle is sore doesn't mean it needs more rest.

Just because because a muscle is not sore doesn't mean it is fully recouperated and ready to be hit again. Quads especially may need up to 9 days to recover.

9 days seems a tad long to me. Although, it's not necessarily a bad thing. I keep it simple. Regardless of body part, everything gets 7 days, unless I'm switching up my schedule which may throw things off by a day or two just for that week. One or two body parts per day Mon-Fri. Rinse and repeat. No overtraining.Just because because a muscle is not sore doesn't mean it is fully recouperated and ready to be hit again. Quads especially may need up to 9 days to recover.

Overtraining really has nothing to do with soreness anyway and there are different types of soreness. Lactic acid build-up causes soreness and micro-tears in the muscle cause soreness. They feel completely different and go away at different rates. Back when I used to spend 90 minutes in the gym doing 10-15 sets of everything, I would be sore for 2-5 days. That was lactic acid. Now I just get micro-tears and that soreness only lasts a day or so.

And I still let the muscles recover for 7 days. That's just the method I use.

DriverDan

Member

- Awards

- 0

Can you cite research to back that up?Just because because a muscle is not sore doesn't mean it is fully recouperated and ready to be hit again. Quads especially may need up to 9 days to recover.

I don't think that it is a good idea to start quoting general time requirements (days) for recovery since it is highly individual based on genetics and training regimen. Training heavy and to failure is hard on the CNS but may not have concurrent muscle soreness. HST on the other hand cycles reps/weights, is lower volume, and each muscle group is meant to be trained several times per week. As usual it all depends...

Last edited:

Yep good point. As with anything else, people react/respond differently.I don't think that it is a good idea to start quoting general time requirements (days) for recovery since it is highly individual based on genetics and training regimen. Training heavy and to failure is hard on the CNS but may not have concurrent muscle soreness. HST on the other hand cycles reps/weights, is lower volume, and is each muscle group is meant to be trained several times per week. As usual it all depends...

Can you cite research to back that up?[/QUOT

I'll try and find a source but I do remember reading about this a lot in the past. When muscle soreness subsides that just indicates that the initial damge to the muscle has been healed but it doesn't mean that the new growth to strengthen the muscle has taken place. Just think about it though, if you are an experienced lifter then it is doubtful muscle soreness for say chest will last more then 3 days. If you do chest every 3 days more then likely you will be severely over training because although the muscle feels alright, you still have not given it the time improve and grow which is what building muscle is all about.

i would recomend reading up on dual factor or three factor training. planned overloading of the muscle and CNS leading to short term decreased perfromance is acceptable. It will produce exceptional results as long as it has deloading phases scheduled appropriatly.Just don't workout a muscle thats still sore...even if its a little sore...thats a for sure way to avoid overtraining

What most people expierience is muscle overreaching which has many of the same symptoms as overtraining. overreaching is the a phase prior to overtraining and overtraining is not very common and is something that happens over a long period of time from overtraining.

i think i'll look for some dual factor training to post up here. Fatigue accumulation and training response are defined as two seperate things.Can you cite research to back that up?[/QUOT

I'll try and find a source but I do remember reading about this a lot in the past. When muscle soreness subsides that just indicates that the initial damge to the muscle has been healed but it doesn't mean that the new growth to strengthen the muscle has taken place. Just think about it though, if you are an experienced lifter then it is doubtful muscle soreness for say chest will last more then 3 days. If you do chest every 3 days more then likely you will be severely over training because although the muscle feels alright, you still have not given it the time improve and grow which is what building muscle is all about.

The single factor theory you are describing is a bit antiquated.

Here is some 3factor training while i look for some articles on 2factor training so i don't have to write anything up from memory (or make any mistakes)

Three Factor Model of Adaptation

By Mladen Jovanovic

For www.EliteFTS.com

________________________________________

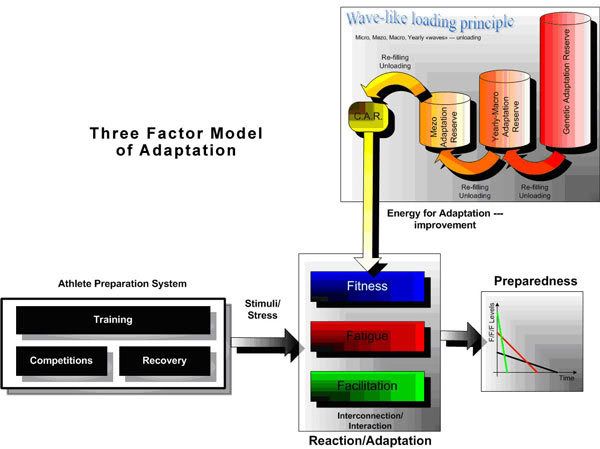

I got the idea to create the three factor model of adaptation (3F) after discussing a thread on central nervous system fatigue. Here is the basic premise:

preparedness = fitness + fatigue + facilitation

Fitness, fatigue, and facilitation are “immediate” and specific effects of a training stimulus. Fitness is the level of a particular trait/ability. It’s the most “inertial” factor. It slowly rises and slowly falls (compared to the other two). Fitness increases the spent current adaptation reserve (CAR) or some form of “adaptation energy,” which should be “refilled” from larger “buffers” during unloading phases. This is one of my premises for wave-like loading and unloading principles. Others include fatigue accumulation, trait synchronizations, rest, and general/specific ratios. Fitness increases are limited by the upper genetic limit and the genetic adaptation reserve (which can be spent prematurely by constant training and stress before even reaching the upper genetic limit).

Fatigue is (according to my understanding) an “expression” (or sensation like RPE or tiredness) of control mechanisms that limit performance to protect the body from damage or death. It can have various forms and properties such as the delayed phenomena in HI CNS fatigue. Like fitness, fatigue is also specific. It’s always a negative sign (contrary to fitness) and is related to fitness. As the athlete advances, he need more stress to produce only a small increase in fitness, but this increase causes a great amount of fatigue.

Facilitation is the shortest effect of a training load. It’s called post-tetanic potentiation (PTP), but it may be also due to arousal or stimulants. Higher facilitation can cause higher levels of fatigue afterward because of higher amounts of taxing on the system. It can have positive effects as well as negative effects on performance depending on the level of it. All three of these factors are conceptual and interconnected.

The speed of adaptation/improvement depends on the “dose-response,” or the amount of work/load needed to increase fitness (and the level of that increase). It also depends on the fatigue created by the same amount of load and the time of recovery (recoverability). So for the best results (at the current point in an athlete’s career), you need to find the optimal workload to produce optimal adaptation while allowing optimal recovery from the same!

Thus, you need to use a minimal load to provide adaptation and fast recovery. If you use larger loads, the fitness will increase more, but it will take more time for fatigue to decline and you’ll have fewer effects. You should search for optimal loading protocols for a given athlete at a given point in an athlete’s career. Note that relations are nonlinear!

The 3F model can explain all of the “modern phenomena” in training better than the dual factor (2F) or single factor (1F) models such as delayed fatigue, fatigue accumulation, facilitation, and unloading needs. Because of the interactions of fitness, fatigue, facilitation, and “energy adaptation drain,” it can be pretty simple to understand the superiority of the conjugate sequence system and the fight of various traits (e.g. strength and speed) for the same adaptation energy!

Single versus dual factor model of adaptation

(Mladen Jovanović, August 10, 2006)

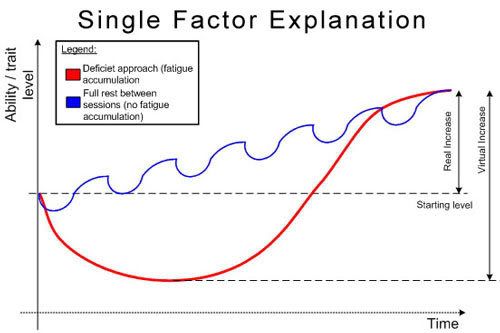

The single factor model of adaptation depicts preparedness (or a single characteristic, ability, or trait) as a single line. After the training stimulus, preparedness decreases. Then, after some time, it “supercompensates” and returns to a normal level and beyond. So, it’s also called the “supercompensation” model. The larger the stimulus, the larger the decrease and thus, supercompensation.

I don’t know how over time people equated the dual factor model with fatigue accumulation (and the provocation of delayed adaptation). The dual factor model and fatigue accumulation approaches to training to produce delayed adaptation are not synonymous! Fatigue accumulation can also be explained by the single factor model and depends on the stimulus strength and frequency.

Fatigue accumulation results in a decrease in preparedness from the starting point and can be explained using both models. This method is proposed by Verkhoshansky. To be honest, I don’t buy it! Let’s take the sprint as an example. Your athletes should sprint without full recovery between sessions, and their performance should decrease over time. You then unload them and wait for the “miracle” to come (long-term delayed training effects). Again, I don’t buy this training approach for speed, strength, or power events. Maybe it works for endurance…maybe.

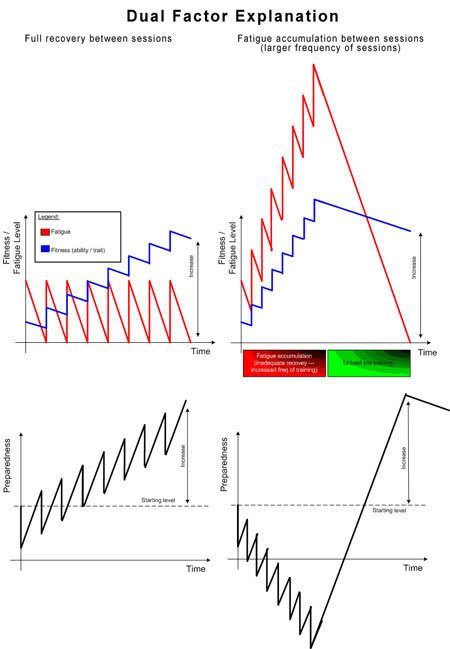

So, during that “accumulation” period, the athletes’ form starts to suck, and they are more prone to injury. They are “learning” to run with poor form. Three words—avoid this approach! The dual factor model depicts preparedness as a “steady” component (fitness) or a “fast” component (fatigue). Preparedness at a given instant of time equals fatigue plus fitness level.

The dual factor model more precisely depicts what is going on and can explain the effect of the tapering and unloading period while the single factor model can’t because there is always some minimal fatigue level in athletes whether or not they tried to train when fully recovered. Thus, there can be an increase in preparedness (and thus performance) from training session to training session while there’s also an accumulation of some minimal level of fatigue. When we unload or taper, the fitness component is kept constant and that minimal level of fatigue decreases. Thus preparedness (and performance) jumps even more. This can be depicted by the dual factor model but not by the single factor model.

Ok, here it is in a nutshell:

1. Single and dual factor models both explain adaptation. However, the dual factor is younger and can explain some things better (like the unloading and tapering effects).

2. The dual factor model is NOT synonymous with the fatigue accumulation approach to training. Fatigue accumulation can be explained by both models.

3. Fatigue accumulation sucks! Preparedness (visible as performance) should become better, not worse over time. Sprinters should run faster. Lifters should lift heavier. Jumpers should jump higher/longer over time, not worse over time. Fatigue accumulation is “playing with fire.” Fire is useful, but it can burn!

4. Do NOT equate the conjugate sequence system with fatigue accumulation! Training blocks of unidirectional loading are done with elite athletes to provide the adaptation effect while maintaining all other previously developed traits. This is a must because elites athletes don’t respond very well to the sequential approach (one trait at a time) because of the “use it or lose it” law. In addition, they don’t respond well to the concurrent approach (all traits at one time) because they can’t respond to a large number of different stimuli (they get pretty fatigued). The solution is to emphasize the development of one single particular trait while maintaining all necessary, previously developed ones. This doesn’t necessarily mean fatigue accumulation. During unidirectional loading, the performance should go up, not down!

5. Although preparedness and thus performance go up, a certain amount of fatigue is accumulated over time (though it’s pretty low). This is why unloading and tapering increase performance before competition. Reduced volumes of training allow fatigue levels to decrease while maintaining the fitness component. The result is an increase in performance. This is easily explained by the dual factor model but not so well with the single factor model.

6. Unloading and tapering aren’t only done to decrease fatigue. Unloading is also done to allow various traits/abilities to “synchronize” because of their heterochronic characteristics. Also, it fills the CAR, which is “depleted” by preceding adaptations (that “spent” it). Unloading allows for a “waving” progression, which is one of the training principles. You can’t break principle laws. You can only break yourself on them.

7. I’m not crazy, but I spent four hours drawing this. I enjoyed it but really I should get a life!

simplified but it will work.

2FT: Dual Factor Training

By: Matt Reynolds

Training Theory

Ok, ok, so it's not so bad this time around. In our last article, we not only addressed our fear of training theory, but also embraced the aforementioned lovable communist science and turned it into something that could be useful in the weight room (i.e..- something that will actually give us a leg up on reaching our physique and performance goals).

In the last article I presented a sample program which utilizes 2FT (Dual Factor Training), and in this article we'll break down all aspects of the program to better explain how to make 2FT work for you.

Before we start, let's recap what we've learned so far�.

Supercompensation Theory

Supercompensation theory says to beat the crap out of our muscles and deplete them of all their good stuff (like glycogen, amino acids, creatine, etc.), let them recover for 3-10 days, and provide them with all the nutrients they lost (and then a little bit more).

The result should be that the muscles will store more nutrients than they originally had, and thus will be bigger and stronger.

Result:

Doesn't really work - at least not very well. Unfortunately, it's almost impossible to time your workouts just right, meaning that you either won't rest long enough, which will quickly lead to overtraining, or rest too long, which means that the growth stimulus is lost, and you end up back where you started.

Dual Factor Theory (2FT):

Dual Factor theory, on the other hand, provides a better (and correct) view of training theory. Instead of looking at each single training session as fatiguing, and the few days after it as the recovery period, 2FT views entire periods of training as fatiguing or recovery.

And as I mentioned in the last article, science has shown us that the body makes extraordinary gains when provided with a period of peaking fatigue, or "loading," (2-6 weeks) followed by a period of recovery, or "unloading" (1-4 weeks).

So the most important thing about 2FT is to understand how long and how hard to "load" during the fatiguing phases and how long and how much to "unload" during the recovery phase.

Result:

You can have shorter training cycles, more precisely timed peaks, and generally more progress in both physique and performance goals.

Loading and Unloading

The first thing to remember about the program is that it is setup with periods of peaking fatigue (called "loading"), where you will slowly reach the point of overreaching (near overtraining). In simple terms, during loading periods you will train hard and not allow yourself to fully recover before training again.

By doing this, fatigue will slowly build up in your system until you approach overtraining. These loading periods should last around 2-3 weeks. It's important to note that the program laid out will most likely be fatiguing to just about any athlete, but some may over-reach in only 1-2 weeks, and for others, it might take 3 or even 4 weeks. So it's important to note that what is loading for me might not be loading for you.

In the same manner, if you follow this program and feel like you are overtrained after only a week or so, then you will need to back off a bit and find the right amount of work for you as an individual.

"How Will I Know How Hard To Load And Unload?"

Well, honestly, it's not an exact science. The easiest thing to do is to start this program and load for only one week, and follow it with a one week unloading period. If you felt fine, and never felt like you were overreaching, then try to load for 2 weeks next, followed again by a one week unloading period. If you are still fine, then you could even try loading for 3 weeks, followed again, by just one week of unloading.

I would note, however, that I have found that most athletes do best with a 2 week loading period, followed by a one week unloading period.

For unloading, it's usually best if intensity is kept relatively high. (Intensity is not a perception of how hard you are working, but is a term relating to how close of a % to your rep maximum you are working - therefore, it's important during unloading weeks to still train heavy.)

However, even though intensity is kept high during unloading, volume is drastically reduced, by dropping the workouts from approximately 7 exercises down to only two or three. Frequency (number of training sessions per week) is sometimes reduced, but in this program it's kept the same.

"How Will I Know If I Am Overreaching?"

Well, again, it's not an exact science, but you'll feel lethargic, your joints will probably hurt, and most importantly, the amount of weight you can lift will begin to decrease.

If at any time the weights you are using fall down to 85% or so of your previous best, then you are overreaching (and nearing overtraining), and it's time to start unloading.

Now, sometimes you just have a bad day in the gym, or you didn't sleep well last night, or maybe you've been sick. I rarely make a decision about overreaching after just one bad workout. However, if two or three training sessions go by, and you aren't even getting close to hitting new maxes, then it's time to start unloading.

The goal of this program is to get to that point (or near it) after approximately two weeks of loading. The first week you'll probably feel fine, and you'll get in some good hard workouts. By midway through the second loading week, however, you'll probably start feeling run down, and by the Friday or Saturday session of the second week, you'll probably feel really run down and "beat up."

When you hit that point, then it's time to back off the volume substantially for a week or so and allow your body to recover from the two hard weeks of loading.

If done correctly, the result will be a noticeable improvement in size and strength following the unloading period. Now, obviously you aren't going to notice huge gains after a single three week cycle of this program, but after several cycles, you should begin noticing real differences in your strength and appearance.

Dr. Squat (Fred Hatfield) has some great info on Overtraining Vs Overreaching i would suggest reading at his website. I cannot past it in as it has a copywrite.

When you look like:

This

Instead of this

This

Instead of this

It took me a VERY LONG time to realize I was overtraining several years ago. Machine's post is a exact replica of what my earlier bodybuilding years were.

TheDrive

New member

- Awards

- 0

I don't know about 9 days... but none the less that is a great post! Everyone seems to think that if the muscle is not sore, it has recovered. I recommend a 1000mg Amino Acid Complex at least once a day. I prefer 1 in the morning and immediately before my workout. It takes enough time to digest that it hits my bloodstream near the time that my workout is complete. It's essential for proper recovery. You generally don't absorb enough of the amino acids from your protein supplements. Add the amino complex and you'll feel much better in just a couple days time.Just because because a muscle is not sore doesn't mean it is fully recouperated and ready to be hit again. Quads especially may need up to 9 days to recover.

As for the overtraining topic in general. It's so easy to ignore other signs of overtraining if your muscles aren't sore. If I overtrain, the first thing I notice is I get a bad cold. Water intake and adequate sleep are by far the most important methods of preventing/combating symptoms of overtraining. Protect your immune system!!!

Of course I live and work on a ship...so if one guy is sick, so is everyone else...LOL

DriverDan

Member

- Awards

- 0

Free form amino acids are not essential for proper recovery. Whole foods and protein supplements provide plenty of amino acids. However, free form amino acids are absorbed more quickly and may be more optimal in the workout time period. If you have seen research that suggests otherwise I'd love to see it!I don't know about 9 days... but none the less that is a great post! Everyone seems to think that if the muscle is not sore, it has recovered. I recommend a 1000mg Amino Acid Complex at least once a day. I prefer 1 in the morning and immediately before my workout. It takes enough time to digest that it hits my bloodstream near the time that my workout is complete. It's essential for proper recovery. You generally don't absorb enough of the amino acids from your protein supplements. Add the amino complex and you'll feel much better in just a couple days time.

| Thread starter | Similar threads | Forum | Replies | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Overtraining | Supplements | 55 | |

|

|

Overtraining | Supplements | 2 | |

| Overtraining Workouts at home? | Training Forum | 9 | ||

| Unanswered physical job labourer ... + workout results in overtraining ? | Training Forum | 22 | ||

| Legs feel tight getting weaker overtraining? | Training Forum | 6 |

Similar threads

-

-

-

-

Unanswered physical job labourer ... + workout results in overtraining ?

- Started by costelum

- Replies: 22

-